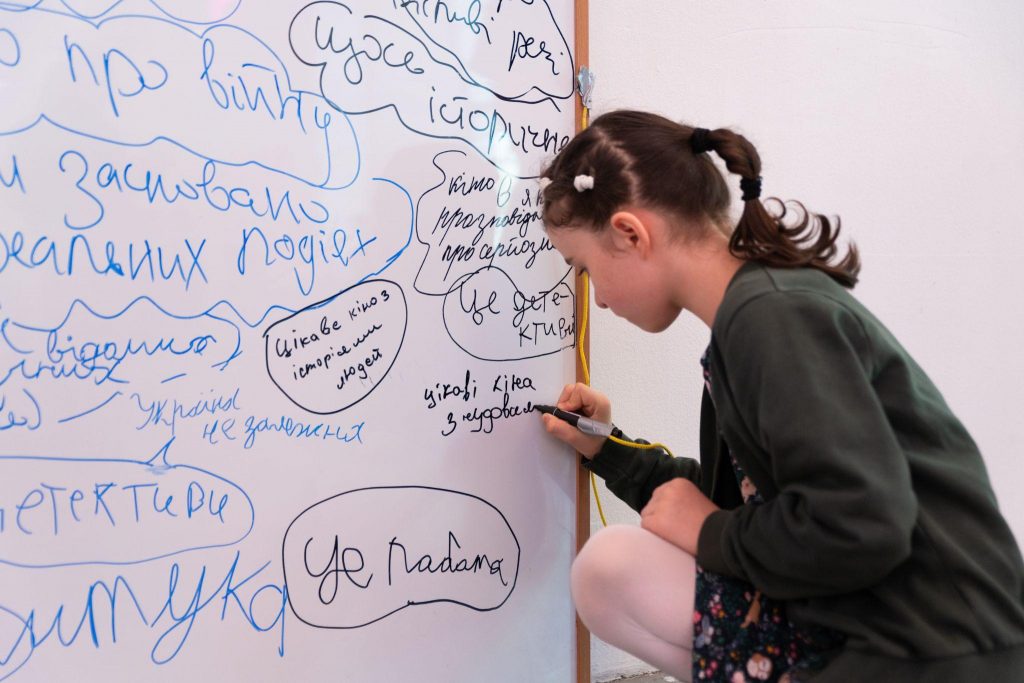

Nataliya Dobryanska, teacher of history, law and civic education and a DOCU/CLUB film club moderator, has been integrating documentaries into her lessons for many years and involving her colleagues in this process. She shared her experience and tips for such integration with the New Ukrainian School. From this material, you will learn: what should teachers consider before screening documentaries in class; why simply watching a film is not enough; how to integrate documentary films into lessons of history, law, civic education and other disciplines. PREPARATION FOR DOCUMENTARY FILMS SCREENING IN CLASS Nataliya Dobryanska has been integrating documentary films into the educational process since 2015. Almost 10 years ago, the teacher came across school lesson materials from the DOCU/CLUB Network. Having adapted them to the needs of her students, Nataliya started using documentary films in her history, law, and civics classes, and even organized a film club at her school. Photo: Nataliya Dobryanska She says that documentary films complement the lessons well, as they help children understand the topic through the prism of real human stories. “However, it's not enough to just show children a film, so that they merely watch it and pass the time in class. A whole lesson needs to be built around the film and its discussion, giving schoolchildren an opportunity to express their opinions, ask questions, and see the film's connections to other subjects. Therefore, teachers need to prepare carefully before the screening,” emphasizes Nataliya Dobryanska. She advises teachers who decide to integrate documentary films into their subjects to: 1. Watch the film before screening it in the class. Analyze whether the film is appropriate for the age group and interests of the schoolchildren. A preview will also help you make sure that you understand the idea of the film, feel confident in the classroom, and can communicate freely with children. By the way, the DOCU/CLUB Network website has an entire collection of Ukrainian and world documentary films about human rights and short annotations to them. Each film page also includes lesson scripts with interactive exercises, teaching materials, and age restrictions. However, the scripts are available only to teachers who have created film clubs at their schools. In addition, schools can join the School DOCU/WEEK coordinated by Nataliya Dobryanska. This is also one of the projects of the DOCU/CLUB Network, which can be joined even by schools that do not have permanent film clubs, and which provides access to documentaries about human rights and volunteering, as well as methodological materials for them. Here you can register your school or class for participation in DOCU/WEEK until September 23, 2024. The event will last from September 24 to October 31. Let's return to Ms. Nataliya's advice for teachers who want to integrate documentary films into their lessons. 2. The length of the film itself should differ depending on the target audience. For 5-7-graders, Nataliya advises choosing short films (up to 20 minutes) because of their age. In their turn, high-schoolers can already “sit through” longer films. 3. When watching longer films, you should take into account the time needed to discuss a particular topic. If you are short on time or do not have the appropriate equipment in the classroom, you can suggest that children watch the film at home and discuss and share their impressions in class later. “Teachers are often skeptical of this suggestion, saying that children will not watch these films at home on their own. Of course, I have no illusions that 100% of the class will watch the film. But from my own experience, I can say that about 50% will definitely watch it. One can already work with this number. We start discussing the film in class, and the schoolchildren who haven't seen the film also want to join, because they become curious and want to be involved. Later, they ask me: ‘May I watch the film before the next lesson?’ So next time, more children will be participating. Just trust the children,” says Nataliya Dobryanska. Photo: Nataliya during the screening of the film Gabriel Reports on the World Cup at the Different Together festival 4. The teacher emphasizes that one should not divide the film into several lessons and watch it in parts. This way, the sequence and the narrative coherence are lost [moreover, this is prohibited by the DOCUDAYS UA copyright agreement – ed.] “Films should be watched as a whole. Because, once again, we do not watch these films just to watch them. We discover the problems faced by the film's protagonists, analyze how they relate to us, discuss, and share our impressions. This process should not be interrupted,” emphasizes the teacher. 5. Before choosing a film, it is important to analyze what topic it corresponds to, what lessons it can be integrated into, and what additional materials or assistance may be needed. According to Ms. Nataliya, you might need to involve one of the other subject teachers, a school psychologist, or even a social worker to better explain and cover the topic from different angles. You can work in pairs with them. “When my pupils and I watched E-Wasteland about used equipment, i.e. electronic waste, much of which is brought to third world countries, in particular to Ghana, I involved several other subject teachers in the discussion. Thus, in a geography lesson, a teacher can speak about the geographical location of a country and its climatic features, in a biology or chemistry lesson – about the harmful effects of garbage on the environment, in history lessons – consider the historical background of the country and its political system, etc.”, says Nataliya Dobryanska. It would be even better, she continues, if these lessons were to follow each other. This will allow the viewers to consider the film from different perspectives. 6. It is advisable to give children homework after watching the film. For example, to draw a picture of their impressions of the film, to write a letter to the main character, etc. 7. Finally, it is important to reflect on the film and the topic in general. Photo: Interactive activities with children at the Different Together festival “At this stage, it's not enough to just ask whether the children liked the film. This is not a reflection. Let's be honest, most of them will say they liked it anyway, because it will make the teacher feel better. Therefore, it is important to ask a right question: What exactly did you like/dislike about the film? Why? Whom would you like to tell about this film? That is why it is important to do everything step by step and be clear about: who are you screening the film for? what precisely are you screening? what is your goal? what do you want to convey with it? SOME EXAMPLES OF INTEGRATING DOCUMENTARY FILMS INTO HISTORY, LAW, AND CIVIC EDUCATION LESSONS History + law “For example, let's take the 10th grade and the topic of the Second World War and the Holocaust. This is a complex theme. Some discuss it by only using the language of facts and dates, or by showing terrible images. However, this does not always explain to children what really happened. This is mostly general information, and scary images are not always the best way to illustrate the story, especially nowadays, when there is a high risk of retraumatization due to children's own experience. That's why I use the animated film Broken Branches from the documentary collection,” the teacher shares. This animated film tells the story of a 14-year-old girl who was forced to leave her home in Poland and travel to Palestine on her own on the eve of World War II. Her family was supposed to join her the following year, but the war broke out. The film is just 15 minutes long. This allows teachers to watch it with their pupils right in class, using it as an introduction. “I noticed that, after watching this film, the topic of the Holocaust became much clearer to schoolchildren. Behind the numbers and facts, they saw real people who lived through it all. The film illustrates and elaborates on the topic well. As a rule, such complex events appear oversaturated in textbooks. Sometimes, teachers themselves find it difficult to start a conversation on a complex topic, and documentaries can help with this,” says Nataliya Dobryanska. The film can also be discussed in law classes when studying topics about human rights. It touches on such topics as minority rights, equality and discrimination, and totalitarian regimes. Law + civic education + world history Another film that allowed Nataliya to integrate three subjects into one is Gabriel Reports from the World Cup. This story of a boy from Brazil who loves football shows how the event affected the lives of local residents through the prism of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, which took place in his country. In order to attract hundreds of thousands of football fans, Brazilian authorities decided to build a railroad through the neighborhood where the protagonist lives. Families were forced to move, and the playground where the boy used to play football was on the verge of destruction. The protagonist, outraged by the inequality in his city, posted a video on his blog of bulldozers demolishing his neighborhood. He tried to publicize the situation and protect his rights. Photo: Ms. Nataliya during the screening of the film Gabriel Reports from the World Cup at the Different Together festival The film touches upon the following topics: the citizen and the state; environmental protection; local self-government; human rights; children's rights. As you can see, the film can be integrated into law lessons when discussing children's rights. Together with children, you can peruse the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and compare it with the issues raised in the film, suggests Nataliya Dobryanska. It can also be screened at world history classes when studying the history of Brazil. It will help children form a preliminary image of the country, its system, and modern life, and then you can delve deeper into its history, the teacher says. The film can also be used in civic education in the context of human and child rights, volunteering, and civic engagement. “Through real-life examples, children will see that, even at this age, they can and should change something and influence life in their yard, village, community, city, or even country. Photo: Ms. Nataliya and DOCUDAYS UA at the Different Together festival Seeing such examples motivates them much better. They start discussing, sharing their opinions, looking for more information about an event or a person. That is, they become interested in the topic and, therefore, in the subject itself. And this is the most important thing,” says Nataliya Dobryanska. The second film that the teacher has also integrated into these subjects is ABC. The main theme here is the rights of the child, in particular, the right to education. The story centers on 19-year-old Wele from Liberia, who wants to learn to read and write in order to keep up with her seven-year-old daughter. “This topic can also be considered from different angles. Discuss why women in some countries still have no right to education; ask what children know about Liberia. In the context of history, you can look at the civil war that was going on in the country, etc.”, Nataliya Dobryanska gives some examples. Documentaries can also be shown at integrated courses in grades 5-6, as part of elective classes or clubs. For example, in the course “Exploring History and Society,” there is a topic on civil and human rights. In this way, children aged 11-12 can more easily grasp complex topics through films where the main characters are their peers. Indeed, due to this format, children remember the information and understand the topic much better, the teacher says. According to Nataliya Dobryanska, sometimes they are so immersed in the film and its discussion that they don't even notice when the break begins. Photo: Ms. Dobryanska and DOCUDAYS UA at the Different Together festival “When my 11th grade and I started talking about the Second World War at the beginning of this school year, one of the students immediately recalled a film about the Holocaust that we had watched earlier. That's when I realized I was doing the right thing. At first, schoolchildren were quite skeptical about documentaries, saying that they were boring. But now their opinion has changed dramatically. They saw that films can be used to combine different subjects and look at a topic from different angles, and they learned to express their opinions and participate in discussions. These skills are much more important than just a good grade or knowledge of chronology. After all, without understanding the broader context, knowing the dates is of little use,” the teacher summarized. Iryna Troyan, New Ukrainian School All photos in the text taken by Maria Brykymova, NGO Smart Education This publication was prepared with the financial support of the German Marshall Fund of the United States of America. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the NGO Docudays and do not necessarily reflect the views of the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

According to her, such questions help summarize the lesson and ensure that children have understood everything. If you simply turn off the TV, multiboard, or any other media after watching the video and immediately move on to another topic, children will ask a logical question: “What's the point of all this?”.

“CHILDREN DON’T EVEN NOTICE WHEN THE CLASS ENDS”: A TEACHER FROM LVIV TELLS ABOUT HER EXPERIENCE IN COMBINING DOCUMENTARIES WITH SCHOOL SUBJECTS

24 September 2024

Did you know that screenings of documentaries can be successfully integrated into a school curriculum? What is more, it allows children to better comprehend the topic of the lesson through the prism of real human stories. It also teaches schoolchildren to express their opinions, ask questions, and participate in discussions.